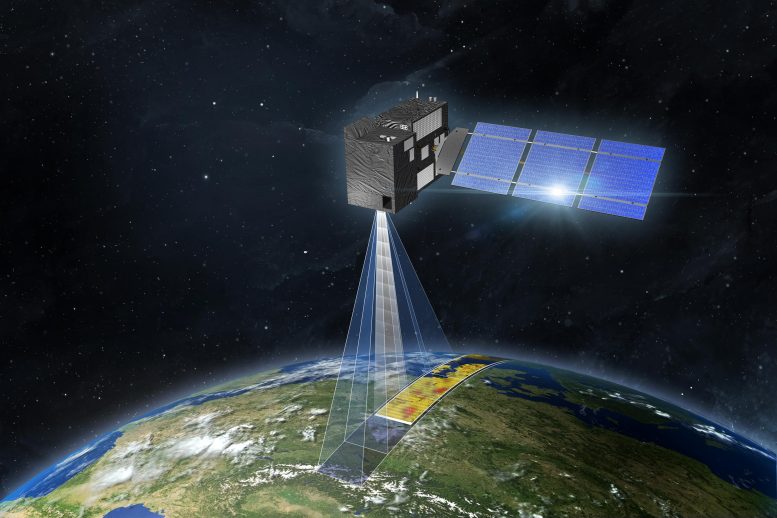

La Misión de Monitoreo de Dióxido de Carbono Copernicus, o CO2M para abreviar, es una de las misiones de Expansión Centinela Copernicus de Europa y será la primera en medir la cantidad de dióxido de carbono liberado a la atmósfera específicamente por la actividad humana. 1 crédito

Capacidad de monitoreo de emisiones cien veces mayor en los próximos tres años.

Los países que firmaron el Acuerdo de París de 2015 se comprometieron a mantener el aumento de la temperatura media mundial «muy por debajo» de los 2 °C. Cada cinco años, deben publicar “Contribuciones determinadas a nivel nacional” (NDC), describiendo sus acciones para reducir las emisiones de gases de efecto invernadero (GEI) y adaptarse a los impactos del cambio climático.

Por lo tanto, los países deberán realizar un seguimiento de sus emisiones de carbono, no solo a nivel nacional, sino también a escala de «superemisores» individuales, como centrales eléctricas, megaciudades, refinerías y fábricas gigantes. Juntos, estos “superemisores” son responsables de casi la mitad de la producción total de GEI de la humanidad.

A finales de 2025 o 2026, la UE tiene previsto lanzar su ‘CO2M’ (Copernicus Anthropogenic CO2 Misión de monitoreo) par de satélites, cuyo trabajo será ayudar con esto.

Importante prueba de principio para CO2M

Pero ahora, los científicos han demostrado que ese seguimiento de fuentes ya es posible, incluso con los satélites existentes, para «supertransmisores» como la central eléctrica de Belchatów en Polonia. Para esta prueba de principio, utilizaron cinco años de mediciones de[{» attribute=»»>NASA’s satellite ‘Orbiting Carbon Observatory 2’ (OCO-2; launched in 2014) and the instrument OCO-3, attached since 2019 to the International Space Station (ISS).

This success is an important achievement, as the OCO missions were designed to measure carbon emissions at much larger spatial scales.

“Here we show for the first time that it’s already possible to measure changes in CO2 emissions from a large power plant, with observations from existing CO2-tracking satellites,” said Dr. Ray Nassar, an atmospheric scientist at Environment and Climate Change Canada, Toronto. He is the study’s first author, published in the journal Frontiers in Remote Sensing.

Largest power plant in Europe

The Belchatów lignite-fired (brown coal) power plant is the largest thermal power station in Europe and the fifth largest in the world. Here, units are sometimes decommissioned and new ones put in service, while more often, units shut down temporarily for maintenance. To be of use, satellites and instruments like OCO-2 and OCO-3 should immediately detect changes in CO2 emissions due to these changes in operation — and here, Nassar and colleagues show for the first time that they can.

CO2 is emitted by the 300-meter-high (1000-foot-high) stacks at Belchatów and carried by the wind in the form of an invisible plume, approximately 10-50 km (6-31 mile) long and 550 meters (1800 feet) above Earth. OCO-2, which orbits the Earth at an altitude of 705 km (438 miles), passes every 16 days close by or directly over Belchatów. OCO-3 orbits at an altitude of 420 km and passes over or near Belchatów more frequently. OCO-3 has the added capability to scan back and forth across a region, giving better local coverage or a wider view.

Not every flyby or overpass is suitable

Satellites can assess the CO2 ‘enhancement’ — extra CO2 emitted by a source — only in the absence of clouds and when the plume doesn’t pass over large water bodies or mountains. They measure ‘XCO2’, the average CO2 concentration across a column directly below, subtracting the current background value (locally, on average 415 ppm) around the plume.

Together, OCO-2 and OCO-3 yielded 10 suitable datasets about the CO2 plume above Belchatów between 2017 and 2022.

Excellent agreement between observed and predicted data

The researchers compared the measurements from space to estimates for Belchatów’s emissions, based on its known daily power generation output. The measurements turned out to closely track the daily predictions. This proves that even today, existing satellites can track emissions in close-to-real time for installations like Belchatów. For example, OCO-2 detected a pronounced but transient dip in emissions from Belchatów between June and September 2021, due to shutdowns for maintenance.

All clear for CO2M

The results are promising: they indicate that CO2M, with a joint spatial coverage about a hundred times greater than OCO-2 and OCO-3, will be able to deliver on future needs.

“The capacity to get the most precise information about CO2 emissions from ‘super-emitters’, such as the Belchatów power plant, across the globe will boost transparency in carbon accounting and hopefully, it will ultimately help to reduce these emissions,” said Nassar.

“This future capacity will lead to improved CO2 emission information at the scale of countries, cities or individual facilities, enhancing transparency under the Paris Agreement and supporting efforts to reduce emissions causing climate change.”

Reference: “Tracking CO2 emission reductions from space: A case study at Europe’s largest fossil fuel power plant” by Ray Nassar, Omid Moeini, Jon-Paul Mastrogiacomo, Christopher W. O’Dell, Robert R. Nelson, Matthäus Kiel, Abhishek Chatterjee, Annmarie Eldering and David Crisp, 28 October 2022, Frontiers in Remote Sensing.

DOI: 10.3389/frsen.2022.1028240

Funding: Jet Propulsion Laboratory, NASA Headquarters